By: Kurnia Ahmaddin

By: Kurnia Ahmaddin

This activity is the contribution of swaraOwa as a member of the Petungkriyono Forest Management Collaboration Forum, which has received the Governor of Central Java’s Decree No. 660.1/26 of 2020. By involving the community, the 2025 biodiversity monitoring activity focuses on 3 villages, namely Mendolo and Kayupuring in Pekalongan Regency and Pacet in Batang Regency. We routinely conduct surveys for a minimum of 7 days per month carried out by 14 local youths. This activity also serves as an effort to assist 5 active hunters in finding alternative sources of income by involving them in monitoring activities or forest patrols.

This activity also aims to increase capacity and promote conservation awareness among communities around the forest, which can transform forest resource exploitation activities into productive economic activities. It involves collecting information on biodiversity, which has great potential to be developed as regional assets and for community-based nature conservation. All data on primate diversity, geospatial information, and other field records are input through the ‘KOBOTOOLBOX’ application. The data obtained from this application has not yet been fully measured using consistent methods. Some reports are contributions from the monitoring team when passing through and encountering primates, so it can be said that this data acquisition is ‘citizen science’ data.

Based on the gibbon population survey in 2021, Kayupuring village is considered a high suitable habitat area for Javan gibbons. Therefore, patrols are conducted by tracking the routes most prone to hunting in the village. A similar patrol method is also carried out in Pacet village, which is the easternmost distribution point of Javan gibbons in the Dieng Mountains. Considering that many forests have been converted into durian and non-shade coffee gardens in Mendolo, patrols are carried out as much as possible by following the movement of Javan gibbons to determine their movement routes, feeding preferences, and behavior in low suitable habitats. The results of this activity are expected to be used as a consideration for tree planting programs, so that tree planting points aimed at Javan gibbons, indicated to be isolated in Mendolo, will have natural crossing corridors in the future.

Over a period of 10 months, the monitoring results recorded by the monitoring team amounted to 242 sightings of 5 species of Javan primates. All recorded geospatial data had an average GPS accuracy of 7.327892 m from the devices used by the monitoring team. By eliminating records of Javan gibbons that were attempted to be followed in Mendolo, as we considered them as a single group, the species with the highest number of recorded sightings was the Javan lutung (Trachypithecus auratus). This species was recorded 75 times, with a maximum of 15 individuals in one group, and an average of 5 individuals per sighting. Meanwhile, the Javan slow loris (Nycticebus javanicus) was the least frequently recorded species, only 3 sightings, with 1 individual observed each time.

The long-tailed monkey (Macaca fascicularis) ranks second lowest in terms of encounter records with 31 encounters. Nevertheless, this species ranks first in terms of the largest number of individuals in a single group, which is 18 individuals with an average of 8.13 individuals. Encounter records with Rekrekan (Presbytis fredericae) amount to 34 encounters, with the highest number of individuals being 16 and an average of 5.059 individuals.

Encounters with Javan gibbons (Hylobates moloch) outside the home range of the group followed in Mendolo were reported 57 times, with an average of 2.54 individuals per encounter and a maximum of 8 individuals observed at one time in the village of Kayupuring. All of these averages and individual counts include sightings and reports of calls heard without seeing the animals, which we counted as 1 individual.

Primates Distribution

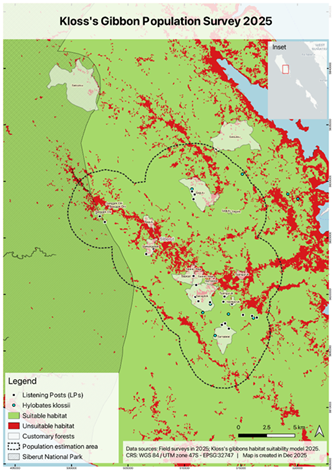

distribution map of the Javan gibbons

The forest area of Kutorojo village, Kajen District, Pekalongan Regency, is a forest region with the westernmost primate records in the Dieng mountain forest area during this monitoring period. This forest area only lacked sightings of the Javan slow loris (Nyticebus javanicus) because the team did not conduct nighttime monitoring when visiting the village. Although not observed directly, based on interviews with the local community, they were able to describe physical characteristics well and even mention the best time to encounter this animal during the peak of the coffee flowering season. Outside this area, the Javan slow loris (Nyticebus javanicus) was only found in Mendolo village during the monitoring period. There were only 3 recorded encounters in forest areas with coffee shade trees beneath, at an average altitude of 624 meters above sea level.

Out of 31 records of encounters with long-tailed monkeys (Macaca fascicularis), 13 were recorded in Mendolo village and 10 in Kayupuring, with an average observation at an altitude of 542.2954 meters above sea level. There was only 1 record at an altitude of 1007.64 meters above sea level in Sawanganronggo, and no encounter reports in Pacet village or other areas above 1000 meters above sea level, except in Sawanganronggo. Although the encounter records indicate that this species’ habitat is quite moderate, ranging from pine, rubber, and durian plantations, encounters in forest areas are relatively low. For example, in Kayupuring, although the habitat is generally forested, encounters with this species are concentrated along the main road. This is likely because at least 4 groups have become habituated to human presence. We still receive reports that local communities and tourists often feed long-tailed monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) along the main road leading to Petungkriyono. Several other reports indicate that groups at the entrance of the forest have started chasing people carrying plastic bags.

The Javan lutung (Trachypithecus auratus) is recorded at moderate elevations and habitats compared to other species in this landscape. It has been observed from an elevation of 404.651 meters above sea level in Kayupuring to 1770.83 meters above sea level in Pacet, with habitats ranging from plantations to natural forests. Meanwhile, records of the Rekrekan (Presbytis comata fredericae) on the western side show an elevation of 393.76 meters above sea level in Kutorojo, and on the eastern side, in Pacet village, it is recorded at 1637.3 meters above sea level, giving an average elevation of 658.2403 meters above sea level from 34 sighting records across the entire monitoring area. The habitat of this species is similar to that of the Javan lutung (Trachypithecus auratus), with even 2 sighting records in tea plantations that have African trees (Maesopsis eminii) serving as shade plants for the tea.

During the monitoring period, Javan gibbons (Hylobates moloch) were only recorded in natural forest habitats with shade-grown coffee plants under the forest canopy. It was reported that this type of primate was found at an average elevation of 596.516 meters above sea level. The lowest recorded elevation was 320.58 meters above sea level in Kutorojo, and the highest was 1566.71 meters above sea level in Pacet. These locations represent the westernmost and easternmost distribution records during the monitoring period. In Pacet, 3 individuals were observed at Silawe waterfall, although they were only recorded once. In Kutorojo 5 individuals were observed in one group.